Summary

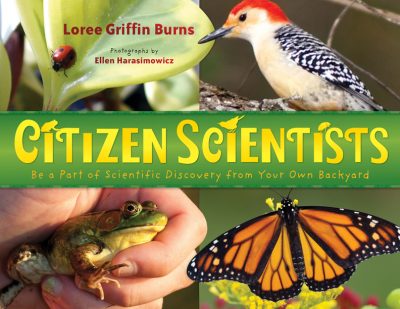

When scientists were trying to figure out where monarch butterflies went in the winter, who helped find the answer? When certain types of ladybugs disappeared and no one knew why, who searched for—and found—the missing insects?

Someone just like you.

You don’t need to be a scientist to take part in real scientific experiments. Just get out into a field, urban park, or your own backyard. You can put your nose to a monarch pupa or listen for raucous frog calls. You can tally woodpeckers or sweep the grass for ladybugs. This book, full of engaging photos and useful tips, will show you how. Through your observations, you can help scientists learn more about the environment. And by learning to listen and watch closely, you’ll find yourself immersed in a year-round world of discovery.

- Henry Holt Books for Young Readers, 2012

- 80 pages

- Ages 10 and up

Honors

- SB&F Prize for Excellence in Science Books

- Green Earth Book Award

- National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Orbis Pictus Honor Book Award

- National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) Outstanding Science Trade Book

- New York Public Library’s 100 Books for Reading & Sharing (2013)

- Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) Choices 2013

- Junior Library Guild Selection

Reviews

School Library Journal, July 2012, Starred Review

An engaging book of seasonal projects for nature lovers (and their parents and teachers as well). Burns explains in her informally sociable text, “Citizen science is the study of our world by the people who live in it.” Beginning with fall, she delves into migratory monarchs, instructing youngsters how to catch, tag, and release these long-distance flitters, and goes on to provide a history and a geography of monarch migration patterns. She introduces two young “Monarch Watchers” (ages seven and six), presents a list of necessary equipment, and offers a quick quiz (answers at the back of the book). She repeats this format for winter (joining in the Christmas Bird Count); spring “frogging” at night (identifying mating calls); and summer (“ladybugging”). Resource sections containing a list of books, field guides, and websites are included for each critter, along with pointers for finding more. Burns is careful to emphasize “gentleness” in catching, tagging, photographing, and releasing specimens. Crisp color photos flow through the pages, many showing kids of various ages hot on the trail of frog sounds or birdcalls. Interested readers will enjoy many of the suggested titles, and a side trip into such elegant offerings as Pamela Turner’s The Frog Scientist (2009) or Sy Montgomery’s The Tarantula Scientist (2004, both Houghton Harcourt) might show them how far these early explorations might lead. Handsome and challenging. –Patricia Manning, formerly at Eastchester Public Library, NY

Kirkus Reviews, March 2012

Citizen-science projects involving butterflies, birds, frogs and ladybugs span the seasons and involve people of all ages in meaningful observation of the world around us. Burns describes the work of scientists who have enlisted the help of children and adults in their work. They tag migrating monarch butterflies in the fall, count birds at Christmas, listen to frogs when the weather warms up and photograph ladybugs in the summer. Project by project, she draws young naturalists in, addressing intriguing instructions for each activity directly to readers. Then she introduces the research, offers a checklist for going out in the field, further information and a quick quiz about each creature. Careful design distinguishes each section of the text by creature and by approach. Colorful photographs show both children engaged in the research and the butterflies, birds, frogs and ladybugs described, including an image of each with appropriate parts labeled with the words naturalists use. The author provides a page of resources for each creature (some written for young readers and some for adults or more experienced researchers) and offers a solid list of other citizen-science projects to be found on line. For curious children and teachers alike, this is an ideal introduction to science activities that leave no child inside. (bibliography, glossary, index) (Nonfiction. 8-14)

Booklist, April 2012

Defining citizen science as “the study of the world by the people who live in it,” Burns encourages children to try four activities, one for each season. In the fall, volunteers can tag monarch butterflies with stickers that help scientists track their migration. Winter brings opportunities for bird-watching and, in particular, the Audubon Society’s Christmas Bird Count. The chapter on spring frog monitoring describes a middle-school field trip that discovered many frogs with deformities and sparked an investigation by scientists. The summer project involves finding ladybugs, photographing them, and submitting information to the Lost Ladybug Project. Throughout this handsome volume, exceptionally clear color photos illustrate the animals mentioned and the adults and children observing them. Though occasionally the book seems better suited to parents and teachers than to kids, the text is clearly written and the idea of promoting science as a rewarding, hands-on activity is a powerful one. Another engaging book from Burns and Harasimowicz, who collaborated on Hive Detectives (2010).— Carolyn Phelan

Horn Book, May/June 2012

Burns brings much-deserved attention to four remarkable scientific projects that enlist regular people in data collection. This participation is not superfluous; the observations of such animals as birds, frogs, and insects, and the careful records made of those observations, are the actual data that scientists use to better understand ecological and life science issues. The projects include stalwarts such as the Monarch Watch butterfly tagging project, started in 1952, and the Audubon Christmas Bird Count, running strong since 1900, but also a recently developed project documenting ladybug species through the uploading of digital photographs and a frog study initiated in part by the discoveries made by some middle-schoolers on a field trip. For each project, Burns gives detailed accounts of the procedures employed by citizen scientists, such as the proper handling of a butterfly or tips on species identification, background information on the animals under study, and profiles featuring experienced citizen scientists. The bright color layouts, encouraging and friendly tone, and handsome color photography of children, adults, and animals in the field make the idea of participation highly appealing. Readers eager to get involved will find information (books, field guides, websites) for these and other projects thoroughly documented at the back of the book; also appended are a bibliography, a glossary, and an index.— Danielle J. Ford