Lights for Your Moth Ball

Humans have invented a dizzying variety of light sources and an equally head-spinning language to describe them. I’ll be honest, I find it all very confusing, even after five years of using lights to watch moths! The thing to remember is that any light bulb is capable of attracting moths on a warm summer night. But bulbs that produce light of specific wavelengths, generally those in the ultraviolet range, will attract the most.

Blacklight bulbs, available at almost any local hardware store, are inexpensive and easy to use. They’re also fun because their shine makes white objects glow dramatically; my younger moth watching friends, especially the ones wearing white shirts or socks or headbands, love this. In my experience, however, these blacklight bulbs are not very good at attracting moths. In fact, they’re not that much better than the regular white bulbs already in your porch light socket. When it comes to moths, ultraviolet light sources are truly the way to go.

In the world of bulbs, ultraviolet refers to wavelengths of light that fall between 400 and 10 nm. While light in these wavelengths is mostly invisible to human eyes, it can damage them if overexposed. Moth-watching revelers should never stare at their lights. Look at the moths instead! And if you’ve got really small children at your event, consider providing protective eyewear rated for UV light. (For example, these.)

Ultraviolet light sources come in an array of types, shapes, sizes and strengths, and they seem to have different names at different vendors. A good place to start your search is companies that cater to bug enthusiasts, like Bioquip.com. I bought their AC Night Collecting Light years ago; it’s a glass tube in a protective sheath that glows purple, includes light in the UV range, and plugs into a standard US light socket. The moths around me seem to like it a lot.

In my experience, however, mercury vapor lamps are the realest of the moth-friendly lighting deals. Professional entomologists and serious moth-watchers spend big money on mercury vapor lamp traps, but this sort of equipment is well beyond the needs of the casual backyard moth watcher. I get by with a mercury vapor bulb purchased at the local pet store, designed to provide basking heat for exotic pets. It’s very important that you have a lamp base that is designed to work with the bulb you select. Like other bulbs, mercury vapor bulbs come in a variety of wattages, and you must select a base that can support that wattage. I have a 160-watt Mercury Vapor Globe from Solar Brite (similar to this one), and I purchased a Porcelain Wire Lamp base from Exo Terra (similar to this one) that can support bulbs up to 250 watts. Conveniently, this wire lamp base has a clipping mechanism that lets me attach the base/bulb combination virtually anywhere, making light station set up easy and portable.

From what I’ve read, the amount of mercury in mercury vapor bulbs is on par with that found in energy efficient compact fluorescent lightbulbs (CFLs) and much less than that found in watch batteries, mercury thermometers, or even dental fillings. There is no danger of mercury exposure while using the bulb, unless it’s dropped and broken. Even then, manufacturers recommend the broken bulb be carefully cleaned up, secured in plastic, and disposed of in the regular trash. (If your town has the option, a hazardous waste facility would likely take it, too.) As with any of the equipment described here, read the packaging that comes with the product and follow the instructions carefully.

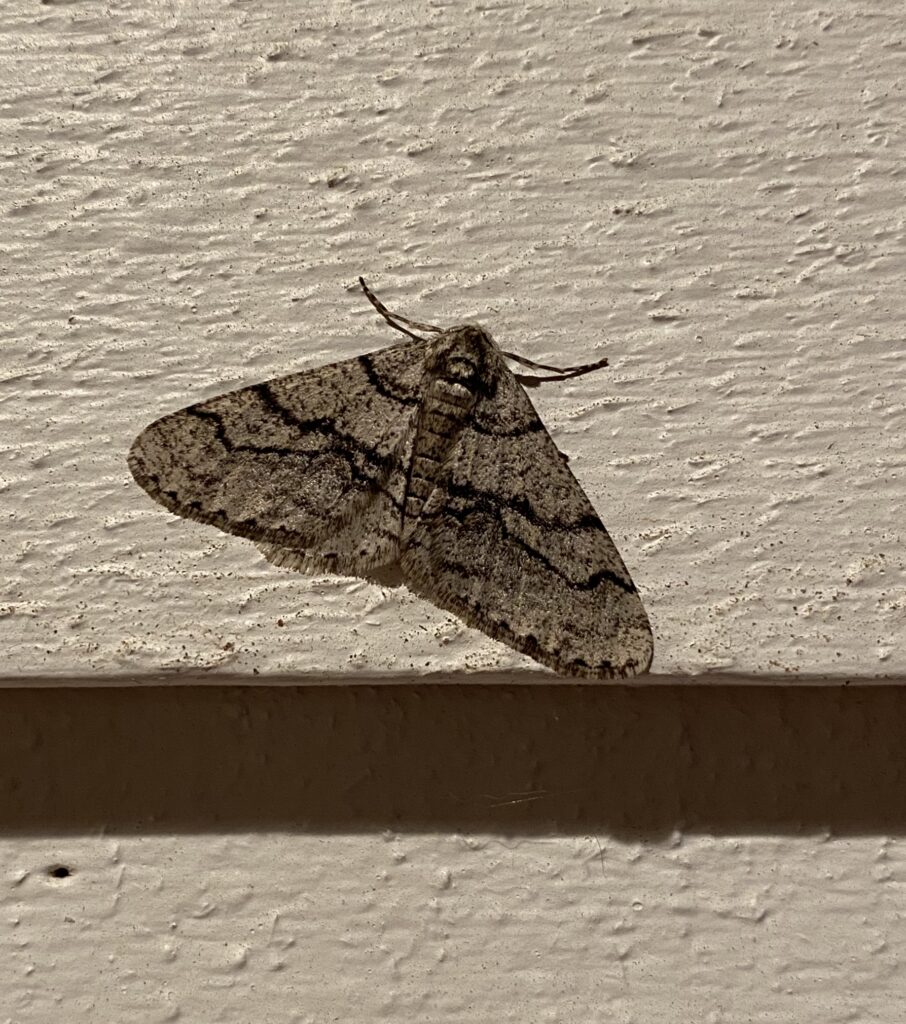

Which moths show up at your lights depends on the lights you choose, where you live, and what time of year it is. Most moths prefer warm weather, which is why summer is the best time for moth-watching. (That said, I found a moth—a half-wing (Phigalia titea)—at my lights in central Massachusetts on March 10 this year! It’s pictured above.) Surrounding habitat will impact the moths you see, too. If there are places near you where moths can thrive, chances are good that some of these moths will visit your light setup after dark.

If you are going to the trouble of sorting out a light source and staying up late to see who it attracts, you owe it to yourself to have a good field guide on hand. I recommend David Beadle and Seabrooke Leckie’s Peterson Guide to Moths of Northeastern North America (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012). Consider supporting local bookstores by purchasing it here. And here are a couple field guide options geared more toward children.

Connecting with other moth watchers is a great way to further your learning and get help with moth identification. There are moth groups on social media platforms (for example, the 13-thousand strong Facebook group called Mothing and Moth-watching; smaller regional groups exist in most places, too) and on the internet (for example, Moth Photographers Group housed at Mississippi State University); seek them out for advice and guidance.

Don’t forget that each July, moth enthusiasts worldwide celebrate Moth Week (July 18-26, 2020), making that a great time to find moth-watching events at nature centers near you. Visit the event website for details.